To complete the news, I need to mention that there is a direct connection with the site editor Dragoslav Simic, and the attachment will explain why.

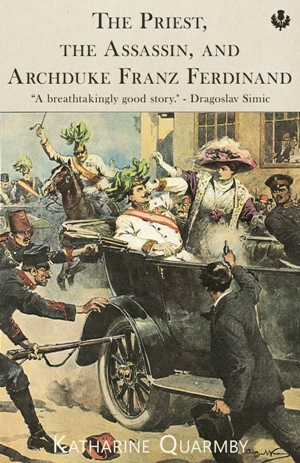

Kosta Božić, priest from Sarajevo, who gave Communion to Gavrilo Princip just before assassination, was a great-grandfather of the English journalist and writer Katharine Quarmby.

Ilustrovana Politika Number

1414 10-XII-85

(The weekly edition of the long-established Belgrade daily paper Politika)

Pages 28 and 29 – An article by Dragoslav Simic.

Translation by Mrs. Isabel M. Bozic, of 6 Woodlands, Harleton, Norfolk.

Rusanj – English style

An Englishwoman spent the Occupation in this village and wrote a book about it, which was not known about until recently. Now local people have set about to find its author “Louisa Rayner”, their friend from war days.

“Dear Madam Louisa Rayner, permit us to send our greetings by the bearer of this letter, from whom we have learnt that you stayed during the war in Rusanj, and that about the life of the inhabitants of our village you wrote a book of those contents we are only partly aware. We earnestly beg you to allow the translation of your book. Our wish is that you would come to Rusanj...”

This letter, in the name of the local community of Rusanj was signed by Miroslav Miloslavljeric. Until recently, neither he nor the villagers had had an inkling that anyone in the world had written about them. The news that a book existed aroused various feelings in the place. The local community, the party organization, the socialist league, the combatants asked whether there wasn’t some trickery in question, or if someone, with who knows what intentions, was meddling in the calm idyllic life of the village. Today the main worry is how to solve communal poverty, how to connect their road to the main Ibar Valley road, to connect up electricity correctly, and then suddenly comes the book which takes them back to 1944. Someone said: “We ought to see how we were described.” Some opposed the letter, but others were curious and conciliatory, so the letter was written.

Spring of 1944

Belgrade, Sava and Danube, Avala. To the right Pinsovava and Rusanj, to the left Kumodraz. That is the geographical sketch with which Louisa Rayner begins her work Women in a Village. By a mere chance in 1958, Bosko Milosavljevic, a translator, bought a copy in South Africa. He now lives in Kumodraz and with his help we turn over the pages.

“Belgrade ladies taking refuge in Rusanj spend their days grumbling about their fate, visiting each other and over barley coffee they criticize the village dirt, lamenting the various shortages. Vida is amazed that, although I am a lady, I don’t grumble about the hard life in the village. She thinks that I ought to be arrogant and intolerant. ‘It is because I am a lady that I don’t grumble’, I said. But I quickly corrected myself. ‘No, it is the other way round. It is because I don’t grumble that I am a lady.’ Clearly the answer pleased her...”

Or: “Chetniks from time to time would come for a good feed at the expense of the peasants. And the feelings of the peasantry towards them could be measured by the ever smaller pieces of the bread and cheese which the villagers had to take out for them to the church green. So the Chetniks devoured their popularity. The peasants of Rusanj managed their community quietly and simply, only offering submission to the earth and the seasons...”

In April 1944 the allies bombed Belgrade. People fled in various directions from those murderous cargoes. Rusanj was then, although fairly near the capital, a secluded village, without roads, which could only be reached by roundabout ways. It was out of range of German Artillery and not important as a target for allied air forces. In the stream of refugees was this English woman who lived in Belgrade with her husband and child. She spent the last six months of the war in Rusanj and later in England she wrote the book.

In her introduction Louisa Rayner writes that she came to Yugoslavia in the 30’s as a tourist. She stayed in Dalmatia and Bosnia and it was in Bosnia that she and her husband were later joined in matrimony. They lived in Belgrade quite close to the cathedral. She had learnt to speak our language and often spent her free time taking her daughter for walks on the Kalemegdan.

Bozic or Rayner?

So it would be possible to say that the book is an excellent record of a vanished period which already belongs to history. But about the writer herself, apart from the bare facts, it gives nothing. The first thing that would occur to the mind of any researchers into the personality of this woman is the question: how old would she be now? And is she still living?

This doubt was quickly solved when an answer arrived from England from Louisa Rayner herself:

“My present name is Isabel Mary Bozic”, she writes. “My married name was Jelisaveta Bozic. But the name Louisa Rayner was my mother’s name, which I adopted for the purpose of the book.”

She was writing in Serbian, in Cyrillic script, and continued: “I must admit that I never expected, after so many years, that anyone in Yugoslavia would have thought my book interesting. Through Mrs. Mary Stansfield Popovic I was appointed to teach English in evening courses at an international club. Belgrade people welcomed me very heartily and I still have happy memories of those days. A knowledge of the English language was much sought after, and I did all I could to learn Serbian as quickly as possible and to fit in with local customs.

In our little old house near the Patriarch’s palace, we were able even from the basement windows, to look out at the broad green meadows from the Sava right up to Zemun, and on sunny days the clear outlines of surrounding hills. In my little drawing room I entertained – with fruit conserve, cakes and coffee – lady friends, English, Serbian and Jewish. And I visited them in the same way, and I quickly learned that little cup of Turkish coffee was a sign that it was time to bring an end to the visit.” The old English woman, Mrs. Bozic, adds to her letter: “My grandsons, who are students, show an increasing interest for their Yugoslav past.”

Long ago, in 1944, the village councillor permitted Jelisaveta Bozic, her husband and child to lodge in the Nikolio house, in which had been born the mother of Marshal Stepe. The house was old and already dilapidated. For water one went a long way to a neigbour’s well. For food one managed how best one could. Borivoje and Dobrivoje were prisoners of war in Germany, and in the house there remained their widowed mother Savka, and her daughters-in-law, Vuka and Vida with their four small children. Those three women are the chief heroes of the story, which is mainly concerned with a description of their characters, their relationships with one another and the fate of the peasants in Rusanj, and even that of the whole Serbian nation. Illiterate Savka fascinates the writer with her wisdom. She calls her a “Queen above women”. Vuka loves the earth. She comes in the evening exhausted but happy after hoeing the fields. Vida looked like a “caryatid”. She had completed primary school and preferred reading to working in the house.

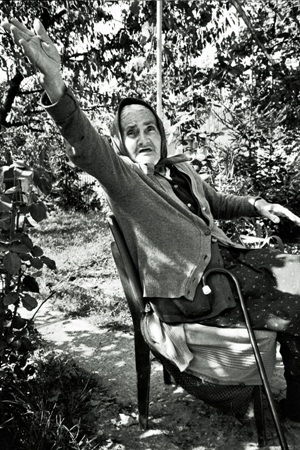

Women in a Village Rusanj. Photo by Dragoslav Simic

1987.

The writer compares their life with that of the ancient heroes. This connection between village life in Rusanj and the classical antiquity of Greece and Rome appears in the very structure of community life.

Thus Savka Nikolic, thanks to the book Women in a Village was known already in 1957 throughout the English speaking world. The London publishers Heinemann was offering the same edition on three continents. The Nikolic family still lives in Rusanj, but old Savka has died. However, the two younger heroines of the book are there, the daughters-in-law, Vida and Vuka.

Vuka vividly remembers the English woman: “Jelisaveta lived with us till the end of the war, until the liberation of Belgrade, then they went back to town, to their house in Fruskagora Street. But I don’t know whether she is still alive”.

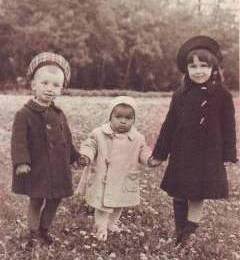

We talk about the village which no longer looks like the old one in the book. Vuka Nikolic’s house is new, like all the others. This talkative old lady proffers fruit conserve and a cup of Turkish coffee does not mark the end of the visit but a welcome to guests. There beside her are her daughters, Milanka, Zivanka and Kosanka, who are mentioned in the book. Milanka and Jelisaveta’s daughter Mara were of similar age. They often played together. When Mara once caught cold the Bozic’s asked Savka to let her sleep in the room instead of in the barn. So they all began to live together and Mara attended the bottom class in the village school.

Old Vuka doesn’t spare words when she talks about Jelisaveta: “If she is still alive, I should like to see her. I should count it like seeing my own daughter. And I should like to see her daughter Mara, because we got on well with them. Even though she was English and an educated woman, she loved to talk with us, especially with Savka. And when in the evening I came in from the fields we would gather round the hearth, and she observed us and enjoyed everything.”

A second witness

A few streets further on, in a big rustic yard, in front of a new house we come across Vida. Even though years have left their mark, this woman’s face reveals her former beauty. After the war she was a dressmaker and a local activist. Her husband didn’t return from the war, and she remembers Jelisaveta:

“She was advanced, always reading or writing something. And to girls who had come as refugees she gave English lessons. In the garden we had beds of pumpkins, and I asked her once: ‘Where did you sleep?’ And she said: ‘In Pumpkin hotel’. She was, so to speak, an old fashioned wife. She always stood beside her husband to serve him while he ate.”

Vida remembers one more detail. Twenty years ago some Americans came there on the trail of Women in a Village. They recognized her from the description. That is all she knows.

On 247 pages are described the life and the people of a small Serbian village. On the title-page one reads the following sub-title “The Impressions and Experiences of an Englishwoman of life in Yugoslavia during the German Occupation”. Below the name of the publisher, William Heinemann, is written “London, Melbourne, Toronto. Year of publication: 1957.” For our native public this book still remains unknown.

Dragoslav Simic

The site

www.audioifotoarhiv.com

is non-commercial and

constitutes a form of

intangible culture.

It is sustained

through donations.

Please support it.

Online editor:

Dragoslav Simić

sicke41@gmail.com

Little Mary Bozic at Kalemegdan in 1940.

latter Katharine Quarmby's mother

About Katharine Quarmby

Katharine Quarmby is a writer, journalist and film-maker specialising in social affairs, education, foreign affairs and politics, with an investigative and campaigning edge.

Her latest book is No Place to Call Home: Inside the Real Lives of Gypsies and Travellers (One World Publications, UK, 22 August 2013).

She has spent most of her working life as a journalist and has made many films for the BBC, as well as working as a correspondent for The Economist, contributing to British broadsheets, including the Guardian, Sunday Times and the Telegraph. She also freelances regularly for other papers, including a stint providing roving political analysis for The Economist, where she has worked as a Britain correspondent, during the 2010 general election.

In 2007 Katharine started to investigate a number of violent killings of disabled men and women across the UK. As news editor of the disability magazine, Disability Now, she was able to put together the first national dossier of such crimes that year, following it up with an investigative report on disability hate crimes, Getting Away with Murder, for the charity Scope and the UK’s Disabled People’s Council, in 2008.

Her first book for adults, Scapegoat: why we are failing disabled people (Portobello Press, 2011), won a prestigious international award, the Ability Media Literature Award, in 2011. In 2012 Katharine was shortlisted for the Paul Foot Award for campaigning journalism, by the Guardian and Private Eye magazine, for her five years of campaigning against disability hate. Katharine and her fellow volunteer co-ordinators of the Disability Hate Crime Network, were honoured with Radar’s Human Rights People of the Year award, for their work on disability hate crime in 2010. http://www.radar.org.uk/people-of-the-year-2/people-of-the-year-2010/the-winners/

Katharine has been interviewed frequently about her work on numerous media outlets, including BBC TV and radio in the UK, the BBC World Service and the Australian Broadcast Corporation. She is also regularly invited to speak at conferences, for organisations such as the Crown Prosecution Service, local police forces, trade unions, charities and Westminster Briefing, the conference arm of the House magazine.

She has also served on an expert advisory committee on disability hate crime to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the Association of Chief Police Officers and the College of Policing.

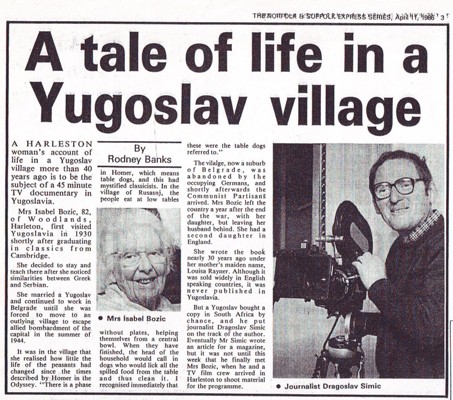

Local newspapers announced that reporters from TV

Belgrade Svetolik Mitić, Feliks Pašić and Dragoslav Simić were recording

documentary film

in Harleston about Mrs Louis Rayner who had written book Woman in a

village about villagers of village Rusanj near Belgrade.

Louisa Rayner stayed in village Rusanj during Nazi-German occupation

in 1944.

(click on picture for extension)

The site

www.audioifotoarhiv.com

is non-commercial and

constitutes a form of

intangible culture.

It is sustained

through donations.

Please support it.

Online editor:

Dragoslav Simić

sicke41@gmail.com

Related links:

About author-editor

Dragoslav Simic

Lujza Rajner

Any responses to or comments on this web page may be sent to the editor of this site: Dragoslav Simic, sicke41@gmail.com. Your correspondence may be published.